Erythroxylum coca: Sacred Medicine, Nutrition, and Cultural Significance

Erythroxylum coca Lam., Erythroxylaceae (the coca family), commonly known as the coca plant, is a sacred, medicinal, and nutritional shrub native to the Andean region ( Peru and Bolivia) with indigenous use documented for over 8,000 years (Nanchoc Valley in present-day northern Peru).4

It is fundamentally distinct from processed cocaine, delivering mild, sustained effects when chewed or consumed as tea, due to slower alkaloid absorption and lower concentrations in the whole leaf.2

Historical and Cultural Context

Indigenous Heritage and Timespan

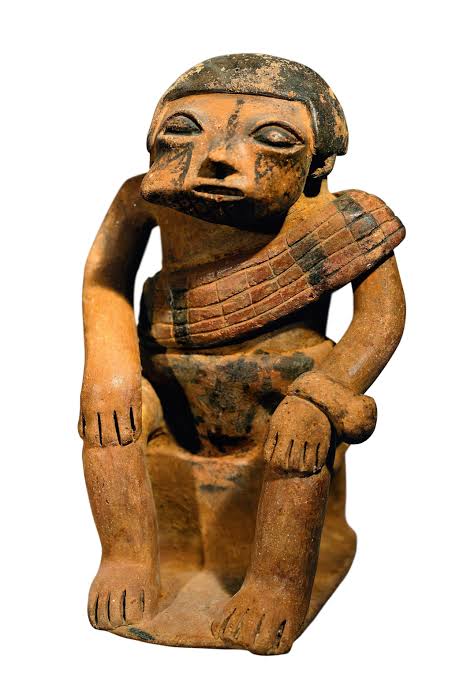

Coca cultivation and use date back over 8,000 years in the Andes and Amazon, as evidenced by archaeological findings and genomic studies of cultigens like E. coca var. ipadu and E. novogranatense var. truxillense.[4]

European accounts from the 16th century CE confirm its role among indigenous peoples for elevating mood, aiding digestion, and suppressing appetite.[1]

For Quechwa and Aymara communities, coca embodies a profound cosmological connection to the environment.4[5]

Sacred and Spiritual Dimensions

Coca serves as a sacred conduit between two-legged (human), natural, and spiritual realms, with chewing ( chacchar, acullicar) forming acts of reciprocity to Pachamama (Mother Earth) and Apus (mountain spirits).[1]

Shamanic curanderos employ leaves for divination, interpreting thrown patterns to diagnose ailments or foresee events.[1]

It also facilitates social harmony, sealing agreements and marking rituals for births, marriages, and funerals.4

Nutritional Composition and Effects

Mineral, Vitamin, and Fibre Content

Traditional Andean knowledge attributes high nutritional value to coca leaves, including calcium for bone health (sometimes compared to milk), alongside potassium, phosphorus, iron, vitamins B1, B2, C, E, and insoluble dietary fibre.[1]

However, quantitative analyses in modern studies are limited; alkaloid content averages 0.72–0.77% (primarily cocaine), with other compounds like methylecgonine cinnamate and hygrine present, but specific mineral/vitamin data require further verification.2

Energy, Appetite, and Metabolic Regulation

Coca provides mild, sustained energy without caffeine-like crashes, suppressing hunger, thirst, and fatigue—vital for high-altitude labour.2[4]

Studies note temporary appetite suppression linked to enhanced glucose availability, potential blood flow improvements, and mild vasoconstriction reducing blood viscosity via atropine-like effects on red blood cell production.[1]

No addiction or withdrawal occurs from traditional whole-leaf use due to low alkaloid levels (<1%).[1]

Medicinal Applications: Traditional and Emerging Evidence

Altitude Sickness (Soroche)

Coca excels in alleviating altitude sickness symptoms (nausea, dizziness, headaches, hypoxia), with mechanisms involving alkaloids that inhibit excessive red blood cell production, reducing polycythaemia and blood viscosity.2 It remains a primary remedy in Peruvian Andes for acute mountain sickness.[2]

Digestive Aid

Traditionally employed as a tonic for ulcers, gastritis, indigestion, diarrhoea, and spasms, coca’s alkaloids may disrupt negative feedback loops in the gut, improving secretions, relaxing muscles, and regulating acidity—similar to hyoscine pathways.[1]

Analgesic and Anaesthetic Effects

Chewing induces local numbness for toothaches, gum pain, and oral lesions; poultices treat wounds and rheumatism.2 Historically used for fractures, childbirth, and surgery before modern anaesthetics; cocaine retains Schedule II status for topical medical use (e.g., ENT procedures).2[3]

Endurance, Respiratory, and Metabolic Benefits

Enhances stamina and reduces fatigue; used for asthma, colds, and potentially blood sugar management.2[3]

Hypotheses suggest benefits for cholesterol/triglycerides and obesity via appetite suppression, though evidence is preliminary.[1]

Cardiovascular Effects

Primarily vasoconstrictive (opposing bleeding, e.g., nosebleeds), with possible blood-thinning via reduced haemoglobin.[1]

Contradicts vasodilation claims; more research needed.[1]

Scientific Evidence: Strengths and Limitations

Research Landscape

Traditional uses are robustly documented ethnobotanically, but clinical trials are scarce due to legal barriers—most data derive from case studies, not RCTs.5

WHO notes insufficient data to confirm solely beneficial effects without risks.[1]

Genome sequences of E. coca (584 Mb) and E. novogranatense (573 Mb) enable future alkaloid biosynthesis studies.[4]

Cancer risk appears low (no DNA damage detected, though alkaline adjuvants may cause cytotoxicity).[1]

Key Distinctions from Cocaine

Whole-leaf coca’s low alkaloid dose (0.3–1.5%), slower absorption, and synergistic compounds prevent addiction, unlike purified cocaine.2 De-cocainised extracts flavour products like Coca-Cola.4

Traditional Usage Methods

Chewing (Chacchar, Acullicar)

Small leaf quids held in the cheek with alkaline ash (llipta/lejía/toqra, or ishcupuro)

to potentiate alkaloids.2

Tea (Mate de Coca)

Brewed for soroche and daily health.3

Poultices

Topical for pain and wounds.[1]

Legal and Regulatory Framework

Coca leaves are legal in Bolivia/Peru for traditional use but prohibited internationally (e.g., UK Class A precursor and US Schedule II source plant). 2[3]

Reflects tension between cultural and spiritual heritage and cocaine’s abuse potential; de-alkaloidised forms permitted industrially.4

Conclusion

Erythroxylum coca exemplifies a plant of immense cultural, spiritual, nutritional, and medicinal value, with millennia of safe traditional use contrasting international prohibition.

Deeper research into whole-leaf profiles could unlock applications for altitude sickness, digestion, and metabolic health, bridging Andean wisdom and modern science—provided legal obstacles are addressed.4[5]

©DrAndrewMacLeanPagonMDPhD2026

( द्रुविद् रिषि द्रुवेद सरस्वती Druid Rishi Druveda Saraswati)

All rights reserved.

PS

Composition of alkaline ash (llipta/lejía/toqra, or ishcupuro)

Lime (Cal):

Typically derived from burnt limestone which is then slaked to create calcium hydroxide.

Vegetable ashes (Ceniza de vegetales)

Most commonly produced from burning quinoa stalks, kiwicha, potato peelings, or specific tree bark.

Other potential additives

May include powdered seashells, burnt animal bones, or, for lejía dulce (“sweet” versions), aniseed and honey or cane sugar.

Production and Use

Traditional form:

The mixture is processed into a paste or solid block.

Modern substitutes

Some contemporary preparations incorporate bicarbonate of soda (baking soda).

Primary function

It serves as an alkaline agent (a base), which optimises the extraction of alkaloids during the chewing of coca leaves.

References

[1] Erythroxylum in Focus: An Interdisciplinary Review (PMC, 2019) – Comprehensive review of physiology, risks, nutrition, and research gaps.[1]

[2] Quantification of Cocaine from Erythroxylum coca (CUNY Academic Works) – Alkaloid analysis, AMS medicinal use.[2]

[3] Erythroxylum coca Knowledge (Taylor & Francis) – Historical medical derivatives, legal context.[3]

[4] Genome Sequences of E. coca and E. novogranatense (Biodiversity Genomes, 2021) – 8,000-year history, cultigens, assemblies (584/573 Mb).[4]

[5] Morphometrics and Phylogenomics of Coca (Oxford Academic, 2024) – Genetic structuring, ethnobotany.[5]

[6] Morphological Studies of Coca Leaves (Biodiversity Library, 1984) – Archeological evidence.[6]

[7] Phylogenetic Inference in Erythroxylaceae (Wiley, 2020) – Species relationships.[7]

[8] Erythroxylum coca (JSTOR Plants) – Botanical references.[8]

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Gaia's Pharmacy with Dr. Andrew Maclean Pagon, MD PhDSubscribe to Awake Events & Posts